- Sugar Biology Online

- List of foods high in sugars US Department of Agriculture

- Calculation of the energy content of foods ─ energy conversion factors Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

- Lee HC et al, 2008, Isomaltose Production by Modification of the Fructose-Binding Site on the Basis of the Predicted Structure of Sucrose Isomerase from “Protaminobacter rubrum PubMed Central

- Tagatose The Sweetener Book

- Touger-Decker R et al, 2003, Sugars and Dental Caries The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition

- Abranches J et al, 2004, Galactose Metabolism by Streptococcus mutans PubMed Central

- Sugar and dental caries World Sugar Research Organization

- Moynihan PY, 2002, Dietary advice in dental practice British Dental Journal

- Health claims: dietary noncariogenic carbohydrate sweeteners and dental caries [21CFR101.80] US Food and Drug Administration

- Belzer LM et al, 2010, Food cravings and intake of sweet foods in healthy pregnancy and mild gestational diabetes mellitus. A prospective study PubMed

- Bowen WH et al, 2005, Comparison of the Cariogenicity of Cola, Honey, Cow Milk, Human Milk, and Sucrose Pediatrics

- Grobler SR, 1991, The effect of a high consumption of citrus fruit and a mixture of other fruits on dental caries in man PubMed

- Lim S eta al, 2008, Cariogenicity of soft drinks, milk and fruit juice in low-income african-american children: a longitudinal study PubMed

- Arora A eta al, 2012, Is the consumption of fruit cariogenic? PubMed

- Grobler SR et al, 1989, The effect of a high consumption of apples or grapes on dental caries and periodontal disease in humans PubMed

- Moynihan P et al, 2004, Diet, nutrition and the prevention of dental diseases World Health Organization

- Khamverdi Z et al, 2013, Effect of a Common Diet and Regular Beverage on Enamel Erosion in Various Temperatures: An In-Vitro Study PubMed Central

- Azodo CC, 2011, Dentinal sensitivity among a selected group of young adults in Nigeria PubMed Central

- Dental Health European Food Information Council

- Schulze MB et al,2004, Sugar-sweetened beverages, weight gain, and incidence of type 2 diabetes in young and middle-aged women PubMed

- Chen L et al, 2010, Reducing Consumption of Sugar-Sweetened Beverages Is Associated with Reduced Blood Pressure: A Prospective Study among U.S. Adults PubMed Central

- Malik VS, et al, 2010, Sugar-Sweetened Beverages and Risk of Metabolic Syndrome and Type 2 Diabetes PubMed Central

- Dumping syndrome: lifestyle and home remedies Mayo Clinic

- Dietary carbohydrates: sugars and starches US Department of Agriculture

- Added sugars Heart.org

- Beverages SugarStacks

- Mitchell, H., 2006, Sweeteners and Sugar Alternatives in Food Technology

- Paes Leme AF et al, 2006, The Role of Sucrose in Cariogenic Dental Biofilm Formation—New Insight PubMed Central

- Corn sugar (dextrose) US Food and Dug Administration

- Utreja D et al, 2010, A study of influence of sugars on the modulations of dental plaque pH in children with rampant caries, moderate caries and no caries Journal of Indian Society of Pedodontics and Preventive Dentistry

- Teitelbaum JE et al, 2010, Triple sugar screen breath hydrogen test for sugar intolerance in children with functional abdominal symptoms National Informatic Centre

- Disaccharide intolerance I National Organization for Rare Disorders

- Thaweboon B et al, 2011, Fermentation of various sugars and sugar substitutes by oral microorganisms Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine

- Neta T et al, 2000, Low-cariogenicity of trehalose as a substrate PubMed

- Giacaman RA et al, 2014, Cariogenicity of different commercially available bovine milk types in a biofilm caries model PubMed

- Kawashita Y et al, 2011, Early Childhood Caries PubMed Central

- Interventions to change diet in a dental care environment Cochrane Summaries

- Malik VS et al, 2006, Intake of sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain: a systematic review The American Journal of Nutrition

- Te Morenga L eta al, 2013, Dietary sugars and body weight: systematic review and meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials and cohort studies BMJ

- Vartarian LR et al, 2007, Effects of Soft Drink Consumption on Nutrition and Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis PubMed Central

- In adults, what is the association between intake of sugar-sweetened beverages and body weight? USDA Nutrition Evidence Library

- Weeratunga P et al, 2014, Per capita sugar consumption and prevalence of diabetes mellitus – global and regional associations BioMed Central

- Te Morenga LA et al, 2014, Dietary sugars and cardiometabolic risk: systematic review and meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials of the effects on blood pressure and lipids PubMed

- Malik VS et al, 2010, Sugar Sweetened Beverages, Obesity, Type 2 Diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease risk PubMed Central

- Pappas A, 2009, The relationship of diet and acne PubMed Central

- Sugars, granulated (sucrose) NutritionData

- Woo HD et al, 2014, Dietary Patterns in Children with Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) PubMed Central

- Aranceta Bartrina J et al, 2013, Association between sucrose intake and cancer: a review of the evidence PubMed

- Borjian A et al, 2010, Pop-Cola Acids and Tooth Erosion: An In Vitro, In Vivo, Electron-Microscopic, and Clinical Report PubMed Central

- Glycemicindex.com

- Fortuna JL, 2010, Sweet preference, sugar addiction and the familial history of alcohol dependence: shared neural pathways and genes PubMed

- Scientific Report of the 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee, What is the relationship between the intake of added sugars and the risk of type 2 diabetes? National Health Information Center

- Imamura F et al, 2015, Consumption of sugar sweetened beverages, artificially sweetened beverages, and fruit juice and incidence of type 2 diabetes: systematic review, meta-analysis, and estimation of population attributable fraction The BMJ

Sugars

Sugar Definition

Sugars are simple carbohydrates, which include monosaccharides and disaccharides [1]. Dietary sugars are edible, sweet, crystalline substances soluble in water [1].

Sugars are not essential nutrients, which means humans do not need to get them from foods to be healthy. All sugars you need can be produced in your body.

Sugars Formulas

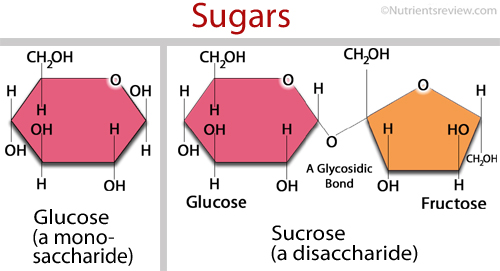

Picture 1. Examples of chemical formulas of two sugars:

Left: Glucose (a monosaccharide)

Right: sucrose (a disaccharide)

List of Sugars in Foods

Calories in Sugars

Sugars provide 3.5-4 kilocalories per gram [3], except isomaltose (<2 kcal/g) [4] and tagatose (1.5 kcal/g) [5].

One teaspoon (4 grams) of table sugar contains 15 Calories [47].

Are sugars “empty calories?”

In fact, calories from sugary foods are the same as calories from other foods. The term “empty calories” refers to low nutritional value of sugary foods (soda, sweets) in the sense that they are often low in vitamins and minerals.

Foods High in Sugars

Picture 2. Examples of foods high in sugars

Sugars naturally occur in high amounts only in plant foods, mainly in fruits and in much lower amounts in vegetables, nuts, legumes, cereals and milk. Sugars are added to certain commercial foods, beverages, medicinal syrups, pills and supplements.

Chart 1. FOODS HIGH IN SUGARS |

|

FRUITS |

SUGAR CONTENT (grams) |

|

20-35 |

| Fresh (1 medium fruit): feijoa, grapefruit, guava, kiwifruit, melon (cantaloupe), nectarine, orange, papaya, peach, plums, pommegranate, rowal, tangerines | 10-20 |

| Fresh (1/2 cup): abiyuch, apricot, blueberries, cherries (sour, sweet), loganberries, mulberries, pineapple; watermelon (1 cup); jams (1 tbsp) | 5-10 |

OTHER FOODS |

|

|

20-35 |

|

10-20 |

|

5-10 |

Chart 1 sources: [2, 27]

Added Sugars

Added sugars are sugars added during food processing. Added sugars may include anhydrous dextrose, brown sugar, confectioner’s powdered sugar, corn syrup, corn-syrup solids, crystal dextrose (glucose), fructose, galactose, high-fructose corn syrup (HFCS), honey, invert sugar, isomaltulose, lactose, malt syrup, maltose, maple syrup, molasses, nectars, pancake syrup, raw sugar, sucrose, tagatose, trehalose and white sugar [25-p.266;26].

Sugar-Free Foods

No Sugar

Foods with no sugar (<1 g/serving) include unprocessed animal foods: meats, poultry, fish, eggs, butter and hard cheese (hard, mozzarella, pasteurized, ricotta). Oils also contain no sugars.

Low Sugar

Vegetables, cereals, bagels, legumes, seeds, nuts, margarine, American, feta, cottage and cream cheese may contain up to 3 grams of sugar per serving.

Fruits that contain less than 5 grams of sugars per serving (1/2 cup, 117 mL): avocado, blackberries, clementines, cranberries, currants, eggplant, kumquat, lime, olives, raspberries, rhubarb, strawberries.

Sugars with Low Glycemic Index

Sugar alcohols (polyols), such as erythritol and xylitol also have low glycemic index.

Rules about claims about sugar content in commercial foods in the U.S. and EU [28-pp.305-6]:

- “Sugar-free” foods should contain less than 0.5 grams sugars per serving (in the U.S.) or per 100 g food (in the EU).

- “Low-sugar” foods should contain less than 5 grams sugars per 100 grams food or less than 2.5 grams sugars per 100 grams liquid (in the EU).

- “Reduced-sugar” foods should contain at least 25% less (in the U.S.) or 30% less sugars (in the EU) than regular foods.

Fermentable and Nonfermentable Sugars

Fermentable Sugars

Fermentable sugars can be fermented (broken down) by yeasts or bacteria.

Bacteria normally present in the human large intestine can ferment fructose, galactose, maltose, mannose, lactose, sucrose and tagatose into gases (hydrogen, carbon dioxide, methane), short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) and other substances. From these sugars, usually only fructose and lactose, which may be slowly absorbed in the small intestine, actually reach the large intestine where bacteria break them down. Fructose and lactose are considered FODMAPs (fermentable oligo-, di- and monosaccharides and polyols), which can cause abdominal bloating, excessive gas (flatulence), loose stools or diarrhea in individuals with fructose malabsorption, lactose intolerance and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).

Fructose, lactose and other fermentable sugars can also cause bloating in individuals with small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO).

Non-Fermentable Sugars

Isomaltose is not fermentable by the intestinal bacteria.

Can sugar be bad for you?

Sugar Intolerance

The term sugar intolerance may include various disorders:

- Disorders with impaired sugar digestion or absorption resulting in abdominal bloating, excessive gas and diarrhea: fructose malabsorption and lactose intolerance. Diagnosis is confirmed by breath tests [32]. Individuals with small intestinal bacterial overgrowth, celiac and Crohn’s disease can also experience symptoms after fructose and lactose ingestion.

- Hereditary fructose intolerance (HFI), a genetic disorder with impaired fructose metabolism.

- Genetic disorders: disaccharide intolerance or congenital sucrase isomaltase deficiency (CSID) with diarrhea in infants after sucrose or starch ingestion [33]

- Allergy to pure sugars is not known.

Sugars and Tooth Decay (Dental Caries)

The bacteria in mouth can break down certain sugars into acids, which can damage the enamel and thus cause tooth decay (dental caries) [6].

- Highly cariogenic sugars (in decreasing order): sucrose [29] trehalulose [34], glucose [30,31], fructose [30,31]

- Lowly cariogenic sugars: lactose [36,37], galactose [7], trehalose [35] and isomaltose [6,9].

- Non-cariogenic sugars: isomaltulose (palatinose) [10,34], sucralose [10], D-tagatose [10]. Other sweeteners that do not promote dental caries and are as such approved by US Food and Drug Administration (FDA): xylitol, sorbitol, mannitol, maltitol, isomalt, lactitol, hydrogenated starch hydrolysates, hydrogenated glucose syrups and erythritol [6,10].

Frequent consumption of foods high in sugars, such as sweets, honey, soft drinks, fruit juices [12,13,14] and, according to some [15,16], but not all [9] studies, even fresh fruits, especially when they represent the main part of the diet [17], may promote dental caries.

Diet cola (without sugars) may also promotes dental caries [18,50]. The risk of dental caries may be reduced by using a straw positioned to the back of the mouth when drinking sugary beverages [19]. Replacing sugary foods with starchy foods (bread, pasta, rice, potatoes) may not help, since starch can also promote dental caries [8,20]. It is the frequency of eating sugary foods and the time elapsed between a meal and tooth brushing rather than the amount of sugar consumed that may increase the risk of tooth decay [8].

According to one Cochrane review of studies the evidence for recommendation to change sugar intake to prevent caries is poor [38].

Weight gain. High sugar intake may be associated with weight gain [21,39]. It is not high intake of sugars alone but high calorie intake that can increase weight [40,42].

Diabetes mellitus type 2. In several systematic reviews of studies, high sugar intake was associated with significantly increased risk of diabetes 2 but the authors were not able to say if the increased risk was due to sugar intake itself or due to the associated weight gain [21,23,41,43]. Authors of the other 2 systematic reviews concluded that the risk of diabetes 2 is associated by the sugar intake itself, independently of weigh gain [53,54].

Blood pressure and heart disease. In several studies, high sugar intake was associated with high blood pressure [22,44] and increased risk of heart disease [45].

Sugar crash or reactive hypoglycemia. In individuals who had stomach surgery, food can pass quickly into the small intestine, which can result in quick glucose absorption, great increase of blood glucose levels followed by quick insulin release and the fall of glucose under normal levels (reactive hypoglycemia). Avoiding meals high in sugar can help prevent reactive hypoglycemia [24].

How much sugar is too much?

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and Institute of Medicine in the U.S. have not set any specific recommendations for sugar intake.

There is insufficient evidence about association between high sugar intake and acne [46], ADHD [48] or cancer [49].

Sugar Craving, Addiction and Withdrawal Symptoms

Sugar craving is an excessive desire to eat sugary foods. Causes may include (anecdotal reports): hunger, habit, sedentary life style, psychological or physical stress (exercise), depression, premenstrual syndrome (PMS), pregnancy [11], low-carb diet, hypoglycemia (low blood sugar), migraine, diabetes mellitus, disorders with loss of glucose with urine (hyperthyroidism, Cushing syndrome, acromegaly).

Sugar addiction is an irresistible craving for sugar. It was observed in some chronic alcoholics and in drug addicts [52].

Sugar withdrawal symptoms (anecdotal reports) may include headache, depression and insomnia.

What may help reduce sugar craving? You can try to be more active (if you have a sedentary life style), quit certain types of foods, such as sweetened beverages, and eat more filling, high-fiber foods. Switching from sugars to artificial sweeteners may not help.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. Do sugars have any health benefits?

Sugars provide about 4 Calories of energy per gram.

2. Which foods can I eat if I am on a low-sugar diet?

Unsweetened whole-grain breads and ready-to-eat-cereals without fruits, unsweetened vegetables, beans, peas and lentils, nuts (except chestnuts), seeds and unsweetened meats, poultry, fish and eggs.

Milk contains lactose, which is a sugar. White breads, pasta, rice and potatoes are similar to sugars, because glucose from them is quickly absorbed.

3. What is sugar detox diet?

Sugar detox diets are various diet plans that supposedly help you to eat less sugar. The term “detox” is misleading, since sugar is not toxic.

Carbohydrates

- Fructose

- Galactose

- Glucose

- Isomaltose

- Isomaltulose

- Lactose

- Maltose

- Mannose

- Sucrose

- Tagatose

- Trehalose

- Trehalulose

- Xylose

- Erythritol

- Glycerol

- Hydrogenated starch hydrolysates (HSH)

- Inositol

- Isomalt

- Lactitol

- Maltitol

- Mannitol

- Sorbitol

- Xylitol

- Fructo-oligosaccharides (FOS)

- Galacto-oligosaccharides (GOS)

- Human milk oligosaccharides (HMO)

- Isomalto-oligosaccharides (IMO)

- Maltotriose

- Mannan oligosaccharides (MOS)

- Raffinose, stachyose, verbascose

- SOLUBLE FIBER:

- Acacia (arabic) gum

- Agar-agar

- Algin-alginate

- Arabynoxylan

- Beta-glucan

- Beta mannan

- Carageenan gum

- Carob or locust bean gum

- Fenugreek gum

- Galactomannans

- Gellan gum

- Glucomannan or konjac gum

- Guar gum

- Hemicellulose

- Inulin

- Karaya gum

- Pectin

- Polydextrose

- Psyllium husk mucilage

- Resistant starches

- Tara gum

- Tragacanth gum

- Xanthan gum

- INSOLUBLE FIBER:

- Cellulose

- Chitin and chitosan

- FATTY ACIDS

- Saturated

- Monounsaturated

- Polyunsaturated

- Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs)

- Medium-chain fatty acids (MCFAs)

- Long-chain fatty acids (LCFAs)

- Very long-chain fatty acids (VLCFAs)

- Monoglycerides

- Diglycerides

- Triglycerides

- Vitamin A - Retinol and retinal

- Vitamin B1 - Thiamine

- Vitamin B2 - Riboflavin

- Vitamin B3 - Niacin

- Vitamin B5 - Pantothenic acid

- Vitamin B6 - Pyridoxine

- Vitamin B7 - Biotin

- Vitamin B9 - Folic acid

- Vitamin B12 - Cobalamin

- Choline

- Vitamin C - Ascorbic acid

- Vitamin D - Ergocalciferol and cholecalciferol

- Vitamin E - Tocopherol

- Vitamin K - Phylloquinone

- Curcumin

- FLAVONOIDS:

- Anthocyanidins

- Flavanols: Proanthocyanidins

- Flavanones: Hesperidin

- Flavonols: Quercetin

- Flavones: Diosmin, Luteolin

- Isoflavones: daidzein, genistein

- Caffeic acid

- Chlorogenic acid

- Lignans

- Resveratrol

- Tannins

- Tannic acid

- Alcohol chemical and physical properties

- Alcoholic beverages types (beer, wine, spirits)

- Denatured alcohol

- Alcohol absorption, metabolism, elimination

- Alcohol and body temperature

- Alcohol and the skin

- Alcohol, appetite and digestion

- Neurological effects of alcohol

- Alcohol, hormones and neurotransmitters

- Alcohol and pain

- Alcohol, blood pressure, heart disease and stroke

- Women, pregnancy, children and alcohol

- Alcohol tolerance

- Alcohol, blood glucose and diabetes

- Alcohol intolerance, allergy and headache

- Alcohol and psychological disorders

- Alcohol and vitamin, mineral and protein deficiency

- Alcohol-drug interactions